The year begins in Panama, which influences the reading selections. Also I have set a goal for myself: I want to read at least one book each week in 2023. #goals

Anderson, C. L. G. "The Darien Colony: Chapter XXIV." Old Panama and Castillo Del Oro. The Sudworth Company, 1911.- I found this old book in the public library in Boquete, Panama. The hard cover was in disrepair but as a source for early Panamanian history, it has a lot to offer. Although I flipped through a few chapters, the only one I read in its entirety was about Scotland's attempt at colonizing Panama in the 17th century. The Scots failed spectacularly but today there are traces of their presence in place names such as Caledonia Bay.

Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. Simon & Schuster, 2013 reprint.

- The last two books I've read (Orlean and Perry, below) have both referenced Bradbury's classic 1950's novel about book burning in an undetermined American future. And since I couldn't remember if I had read this before in college (turns out, I hadn't) this seemed like an opportunity to align the stars. It's a short novel, full of cynicism and dark imaginings. For that, I hated reading it. But the fact that several U.S. states have recently placed it on a list of banned books (coupled with a personal lifetime character trait that enjoys defying authority) means this book is a 2023 must-read. So here it is. In the final moments of the story, one of the characters warns us: "Some day the load we're carrying with us may help someone. But even when we had the books on hand, a long time ago, we didn't use what we got out of them. We went right on insulting the dead. We went right on spitting in graves of all the poor ones who died before us" (156 - 57). Reading Bradbury is an act of remembering, an act of honoring the dead, readers and writers alike.

Foer, Joshua. Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything. Penguin Press, 2011.

- Apparently there is a subculture of geeks who work very hard to remember everything. Foer does a nice job introducing the reader to this subculture, only to find himself immersed in it. I have been interested in the idea of memory for a long time, so much so that I've written blog posts about it. So when Foer rhetorically asks "Socrates thought the unexamined life was not worth living. How much more so the unremembered life?" I knew this was the book for me! It reads fast, and the intersectionality of book culture, medieval philosophies, mental athletes and memorizing techniques makes this one fun and entertaining.

Gappah, Petina. Out of Darkness, Shining Light: A Novel. Scribner, 2019.

- This is a fast and engaging read. Gappah has taken the true story of David Livingstone's death in Africa and fictionalized some of the events surrounding the removal of his body to England by the men and women who accompanied him in the search for the source of the Nile River. It is a unique perspective, inviting the reader to gaze upon the white body of the missionary-explorer from the viewpoint of one man, Jacob Wainwright, and one woman, Halima; both Africans. Towards the end of the novel, Halima reminisces on the impact of the journey in a pensive passage: "I understand now what it means when the urge to travel bites you like a mosquito that gives you a fever that means your feet are never still and your mind is always wandering." As a reader and a lover of travel myself, I completely concur. And now I have set my sights on traveling to the David Livingstone Museum in Zambia. Watch this space!

Gopnik, Adam. Paris to the Moon. Random House, 2000.

- This is a sweet memoir about Gopnik's stint living in Paris in the late 1990s. It's funny, whimsical and introspective. Gopnik offers the reader glimpses of French culture with humor, yet one can't help but feel the depth of his experience from passages like this: "The hardest thing to convey is how lovely it all is and how that loveliness seems all you need. The ghosts that haunted you in New or Pittsburgh will haunt you anywhere you go, because they're your ghosts and the house they haunt is you." In which case, why not be haunted by Paris?

Gregory, Philippa. A Respectable Trade. Atria Books, 2007.

- If the reviews are to be believed, other people have enjoyed this book immensely. But I found the characters implausible and the narrative arc totally predictable. Bought from a used bookstore in Boquete, Panama, I was thirsty to read something in English. When I finished it while on layover at the airport in Miami, I left it under the seat in the terminal. Someone else will probably relish it more than I.

Harris, Jessica B. High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America. Bloomsbury, 2011.

- Whatever you do, don't read this book when you're hungry. Harris does a great job identifying the cultural pathways of Black Americans and infamous culinary delights such as collard greens, sweet potato pie and pigs' feet. Along the way, she provides historical context to food in relation to the slave trade, recipes from Africa, Brazil and the US, as well as some of her own personal experiences on the journey to researching the text. This is a great resource, and one best read after a meal.

Ishiguro, Kazuo. When We Were Orphans: A Novel. Vintage Books, 2000.

- This one's a sleeper! Ishiguro creates an illusion in this slowly unfolding mystery. It begins in the grandeur of British drawing rooms filled with dazzling jewels and substantial meals. The reader is lulled into comfort. But slowly, in increments portioned out by the protagonist's memories, the story shifts to war torn Shanghai in the 1930s. There is no comfort or grandeur to be found, only a sense of loss as the reader realizes (along with the protagonist) the truth of the mystery. The denouement is as surprising as the narrative arc is unique. In short, Ishiguro is a masterful storyteller.

Levy, David W. Mark Twain: The Divided Mind of America's Best-Loved Writer. Pearson, 2011.

- Although I'm not certain he was America's "best-loved" writer, Mark Twain certainly held the American readers' attention for several decades in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is a story teller, to be sure. But the events of his life are somewhat epic in themselves, and likely informed some of his later flair for drama. If you are looking for an interesting biography, this is a good place to start.

Matthiessen, Peter. The Snow Leopard. Penguin Books, 1978.

- Several years ago I read a book by Peter Matthiessen which was so engaging that I ended up writing a review about it. Little did I know then that he is an amazing author with an interesting life story. In this one, Matthiessen writes of his journey (both spiritual and physical) in the Himalayas. At first the reader does not realize that the detours into Buddhist and Hindu theology are relevant to the story. But slowly, as though plodding along high mountain trails in search of a near mythical creature, the narrative arc reveals that not only is this a spiritual journey, but that the physical trials and tribulations Matthiessen encounters on the path are mere symbols of his progress toward Enlightenment. I enjoyed this book. Oh, and he never saw the snow leopard, which I took to be analogous to Enlightenment, but he did manage to see its tracks once or twice. Maybe that's what the spiritual path is all about: seeing the evidence of the divine but only after it has passed by.

McCullough, David. The Path Between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914. Touchstone Book, 1977.

- After hearing about this book while on a boat tour of Lake Gatun, I searched in a couple bookstores in Panama City for a copy in English without luck. But then, upon arriving in Boquete, lo and behold! There is was on the shelf in our Airbnb. It's a good read. The edition I worked my way through is a limited edition printing signed by the author, and appears to have been distributed to passengers on a cruise commemorating the completion of the Panama Canal. Good book, but there may be a newer edition out there. Also, as a final note: it is likely that between 4,000 - 25,000 Black men from Jamaica, Barbados and Martinique died while working to complete the railroad and canal in Panama. They are anonymous to us now, but someone once knew and loved them.

- This is a good book. It's a true story of the Los Angeles Public Library, which tragically burned in 1986, destroying or damaging nearly one million books and other library holdings. The events are well researched and Orlean balances history with a few personal anecdotes and experiences to lighten the heaviness of the topic. Overall, she is a good storyteller. One of the strands of storytelling Orlean develops is the idea of the book (as well as the importance of the library building which holds the book) in society. What a book is, both to the reader and to the writer: "Writing a book, just like building a library, is an act of sheer defiance. It is a declaration that you believe in the persistence of memory" (93). This notion that books hold memory is enduringly interesting, and worthy of much consideration. That Orlean approaches it here makes this book a solid and enjoyable read.

- Perry uses the travel narrative format to investigate some of the cities of the South in the 21st century. This book is part personal exploration, part historical interrogation. It gathers itself to contend with racism, white supremacy, Black resilience and the place of the South in U.S. history. Perry is a terrific travel companion; she contextualizes people, places and events in an easy manner, while elevating Black voices with dignity. One of the things I really like about this book is the way Perry bounces the ideas from other texts and other writers with her own experiences, extending the discussions previously laid out as though all of us (Perry, the other writers, and the reader) are sitting at a coffee shop having a conversation. For example, Perry asserts that "[c]ritical theorist Walter Benjamin once distinguished between two types of storytellers: one is a keeper of the traditions; another is the one who has journeyed afar and tells stories of other places. But there is a third" claims Perry, "and that is the exile. The exile, with a gaze that is obscured by distance and time, may not always be precise in terms of information. Details get outdates. But if the exile can tell a story that gets to a fundamental truth and also tell you something about two core human feelings, loneliness and homesickness, ... then they have acquired an essential wisdom, earning them the title of storyteller" (133). It is this kind of insight - one could say, wisdom - that makes the reader willing to be exiled if that's what is required to obtain it. Don't miss this one!

- Rushdie is a masterful writer. Overwhelmingly, as I was reading this novel, I felt like I was taken care of by a skilled and careful writer. One can hear the characters in the dialogue and patient development of inner monologues. One gets the sense of a narrative arc, yet the end is surprising, nonetheless. Sprawling and engaging, this is a page turner.

- This is a really well written piece of rubbish. Normally I don't read romance novels (probably for the same reason Cervantes despised them), but I was desperate to read something in English. This book just happened to be on the shelf in the Airbnb in Boquete where I was staying. So, I read it. If you are ever as desperate as I was, then I suppose you could read it too.

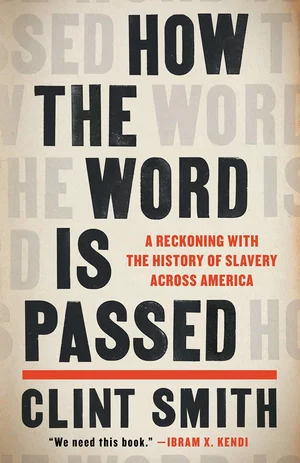

- Excellent books stay with the reader for a long time. Clint Smith's journey through the legacies of slavery is as much poetry as it is memoir. Compelling. Honest. Well-documented. Smith brings it to the reader even as he travels from Texas to Florida to Senegal and beyond on his own personal voyage, concluding with this passage: "My grandparents' stories are my inheritance; each one is an heirloom I carry. Each one is a monument to an era that still courses through my grandfather's veins. Each story is a memorial that still sits in my grandmother's bones. My grandparents' voices are a museum I am still learning how to visit, each conversation with them a new exhibit worthy of my time" (Smith 288). Don't miss this one.

- A word of caution: when setting yourself with a goal of reading one book each week it is not advisable to attempt a 700 page autobiography of wordy-man Mark Twain. What was I thinking? All said, though, this is an interesting collection of Twain's work. One of the more compelling aspects of it is that Twain prohibited his autobiography to be published in its entirety until 100 years passed after his death. He was concerned about offending people with his honesty. It's a good book and I learned a lot about the man that I did not know. For example, he struggled with money, yet appears to have had access to enormous sums throughout his life. If reading such a tome as this needs incentive, then try out this sentence as a taste of the exquisite kind of writing you'll encounter: "In London poor old ragged men and women go up and down the middle of the empty streets, Sunday afternoons, singing the most heart-breakingly desolate hymns and sorrowful ditties in weak and raspy and wheezy voices -- voices that are hardly strong enough to carry across the street -- and the villagers listen and are grateful, and fling pennies out of the windows, and in the deep stillness of the Sabbath afternoon you can hear the money strike upon the stones a block away" (115).

- This is a book about leaving. Sometimes it's written in the first person, whereby Tokarczuk shares travel stories with the reader, personal episodes in the life of a traveler. In other instances, the action is of a woman leaving her husband; or a husband leaving his wife by dying. The reader gets the sense that these events intersect with Tokarczuk's life, but there is no certainty. Indeed, that is the overarching theme here: of the impermanence of living, whether from a suitcase or in relationships. It's whimsical, sometimes funny, occasionally melancholy.

No comments:

Post a Comment